Soteriou Story

Soteriou Story

Journey to Uncover Papermaking Traditions

My first night in New Delhi, the guesthouse had no rooms so I slept on the rooftop. The second night I found the only lodging was a bed in Gandhi’s leprosy hospital after a flight and ox-cart ride transported me to village Wardha. Thus began my lifelong journey to learn more about the history of the humble craft of papermaking. A book dealer’s gift of a tattered book about Indian papermaking (Paper Making, K. B. Joshi, 1947) inspired my quest and a 1984-85 Fulbright award supported my first journey to India.

Before that trip my undergraduate degree focused on anthropology and journalism, and I had apprenticeships at the Center for Book Arts and with papermaker Douglass Howell, along with book restoration training and many related workshops and studies. I received grants and awards from The National Endowment for the Arts, New York State Council of the Arts, and the New Jersey State Council on the Arts. In my own bindery and small paper mill I repaired books and created paper art. I also lectured and exhibited widely. But the shock of India turned my focus to three decades of involvement with paper artisans in India and neighboring locations.

Soteriou with camera in Village India

Soteriou with camera in Village India

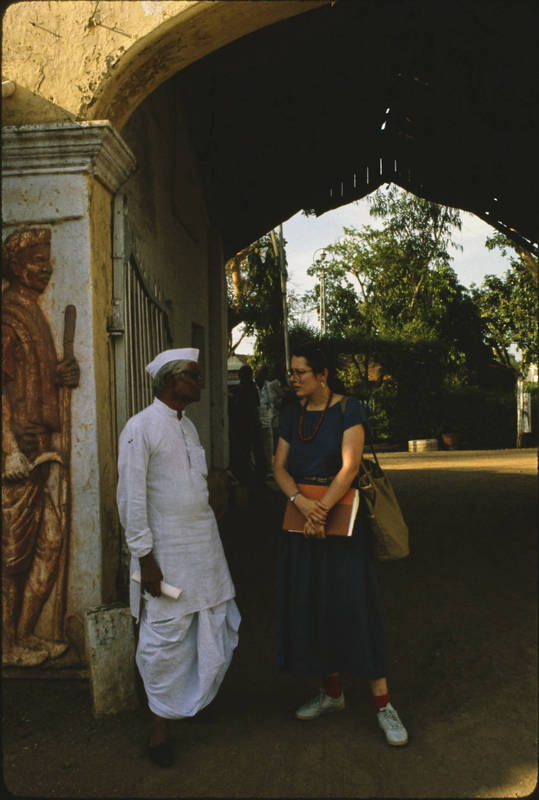

At the Gandhian hand papermaking unit, All-India Village Industries Association (AIVIA), in Wardha, and neighboring Center for Science and Village Industries where Gandhi once lived, I met S. B. Khodke. He became my guide. Khodke was a retired papermaker from AIVIA, later renamed, Khadi and Village Industries Commission, (KVIC). Their paper was made from rags using western type moulds with a lift box system. Hand papermaking was a part of the Gandhian vision for rural self-sufficiency.

Soteriou with Gandhian papermaker S. B. Khodke at All-India Village Industries Association gate

Soteriou with Gandhian papermaker S. B. Khodke at All-India Village Industries Association gate

The eye-opening journey with Khodke spanned much of India. I was searching for what was lost and Khodke knew many places where traditional paper was made in the distant past. This was a start.

To my amazement ruins from the old ways of making paper littered the landscape. In India the past and present often mingle closely. But the panoramas of ruins were a surprise because I had been repeatedly told that there was nothing left of historical papermaking.

Emotional interviews with elder papermakers who lamented the loss of the skilled occupation they were known by and loved touched my heart. They inspired my continued effort to gather the story of their legacy before it was lost. My love of the culture, history, art and traditions of the region also played a part.

The last name, Kagzi, derived from kāghaẕ, the Persian word for paper, identified individuals as a papermaker, coming from a family of papermakers, taught from father to son often going back generations.

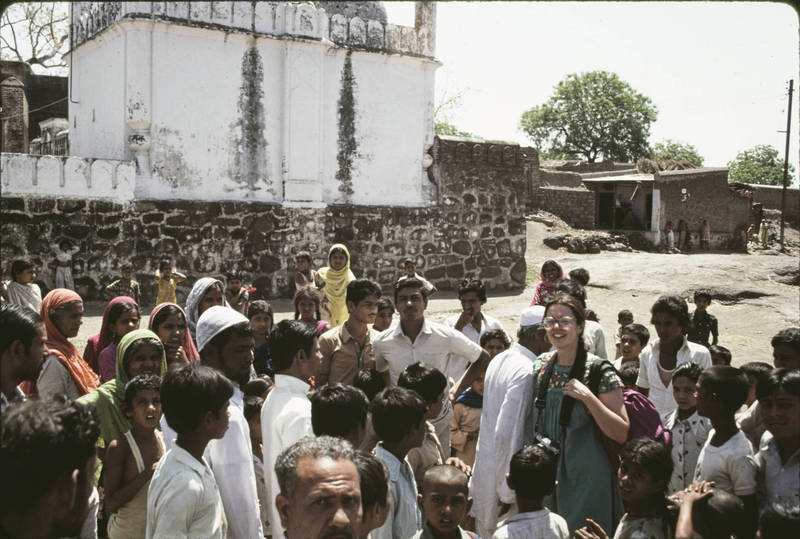

Soteriou in Hathras searching for Kagzi families

Soteriou in Hathras searching for Kagzi families

Surnames became the key I used to track down traditional papermakers during the many trips that followed my first journey in 1985. I chose to explore locations with a storied past known for culture and works on paper. I further refined my focus to areas with a water supply for sheet forming. My academic background in anthropology gave me methods for fieldwork and gathering and corroborating oral tradition.

I found ruins from papermaking activity littering the grounds near centers of culture and art. Why was that important? It revealed a significant amount about the process and the connection to signature ways of papermaking linked to Muslim artisans who migrated through central Asia into the subcontinent. The ruins revealed the early ways of making paper with fermenting pits and pit vats similar to those found in old China. Paper’s historic pathway through central Asia and into the subcontinent became clearer.

Deeply special to me were the conversations I had with many elder kagzi papermakers in quiet villages, who told about their ancestors who were papermakers along with details of their migrations over generations. These kagzi men described in detail and often demonstrated the techniques they used, many no longer practiced. Their lament was that with modern machine made paper, they were no longer able to practice the craft that had been their life activity and that of their ancestors. Kagzi men were always the sheet formers. Kagzi women wove the reed mould surfaces used for sheet forming and they sometimes also polished or hand-sized paper.

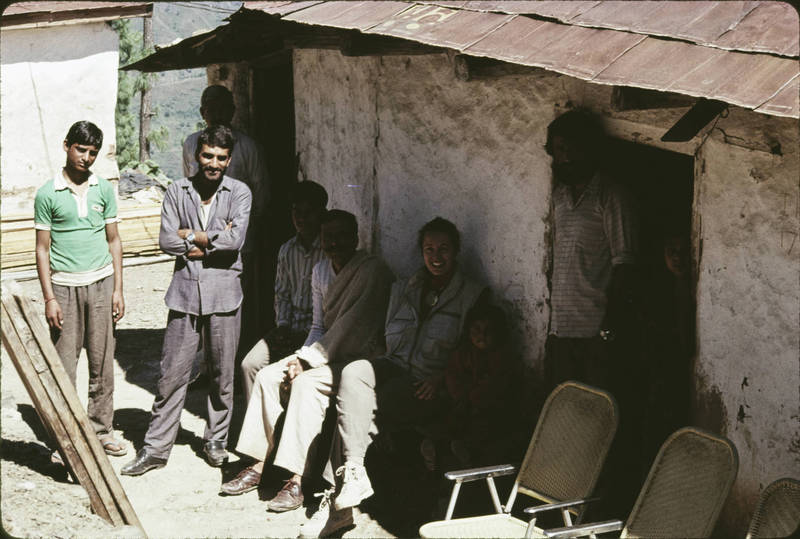

Soteriou in mountains of Shimla learning about mountain fibers for papermaking

Soteriou in mountains of Shimla learning about mountain fibers for papermaking

Despite frugal means I did everything possible to keep returning to India to uncover and record more about the rapidly disappearing papermaking traditions. One trip, long before today’s crowd sourcing platforms, was supported by individuals from the American papermaking community in response to my letters for help. The resulting trip enabled me to continue my fieldwork and start preparing a book using a word processor in the days before Microsoft Word. In 1999 Gift of Conquerors, Hand Papermaking in India was published by Mapin.

I returned to India in 1990 as a consultant for a UNIDO and KVIC project created to help revitalize Indian hand papermaking. My focus before this had been on history and old traditions, but that trip began a new focus on production skills, sales and marketing. During my time with the UNIDO project I was instrumental in getting land donated so a paper center could be built in Sanganer, although I longed for a more decentralized approach that favored local diversity.

Following the project I got a fine American paper company to support Sanganer papermakers with an order for paper sheets and stationery. When the first shipment arrived in the USA it didn’t meet that company’s expectations and I ended up with a garage full of paper products. By necessity, not plan, in 1992, I started World Paper, Inc. to market the paper. Funds from the village papermakers helped me buy a fax machine and I was off and running!

During the years that followed the Sanganer papermakers I worked with flourished. There was a saying in India that goes something like, “If a drop of water falls in a pond, everyone hears it.” That couldn’t have been truer. When others witnessed that success many similar endeavors were established and flourished spurred on by a decade of market trends that favored handcrafted goods. Market trends ebb and flow and recent digital age preferences have moved away from paper use. There are always exceptions. There are quite a number of papermaking units in 2016 when this website first came online. Papermaking in Sri Aurobindo’s Pondicherry location had a long storied past and continues to have a thriving ongoing operation.

During my years of involvement I worked with Nepali papermakers through a USAID project, with Uzbek artisans through an Aid to Artisans project, and with Thai, Nepali, and Indian papermakers for World Paper, Inc. I also arranged to bring together artisans from Uzbekistan, Turkey, Nepal and India, in Jaipur, to learn from each other and share papermaking and marbling methods.

This website provides free use (with required attribution) of images that visually tell the story of the artisans, their history and their methods. Images may be adjusted to compensate for exposure issues.

I am deeply grateful to The Islamic Manuscript Association (TIMA), for their 2015 grant to digitize my slide images, to Tim Barrett for all his support and to the University of Iowa for their part in this website which makes my papermaking images freely available.

Lastly I thank the Indian artisans who inspired my rather unusual life journey!

Alexandra Soteriou

November, 2016